"Spiritual Well-Being, Self-Esteem and Intimacy Among Couples Using Natural Family Planning"

Background of Study

A little over twenty years ago, Marshall and Rowe conducted one of the first studies on the psychological aspects of practicing NFP.3 The study was conducted because of a concern with the "psychological repercussions" that might occur with abstinence from coitus as required with the use of the Basal Body Temperature (BBT) method ofNFP. They administered a detailed psychological questionnaire to 502 couples who were using BBT to avoid pregnancy. Of the 502 couples 410 (82%) returned the questionnaire. Their results showed that 48% of the respondents experienced psychological stress from periodic abstinence or felt other unfavorable side effects on their relationship with their spouse.

Since 1970, a number of modern methods of NFP have been developed to aid couples in regulating conception. One of the most widely known is the Ovulation Method (sometimes referred to as the Billings Method). This method, which involves the daily observation of cervical mucus, was first introduced into the United States in the early 1970's.[4,5] In the mid and late 1970s, Hilgers, Daily, Hilgers and Prebil researched and refined the ovulation method and developed a standardized version now known as the Creighton Model (CrM).[6] The newer methods of NFP are less restrictive in the length of required abstinence than the older BBT method studied by Marshall and Rowe.

A number of studies and reports have shown that periodic abstinence from intercourse does not cause psychological distress among couples who are using modem methods ofNFP to avoid pregnancy.[7,8,9] In fact, abstinence is thought to enhance a married couple's relationship.[9,1O,1l] McCusker found that in 98 couples NFP contributed positively to the marital relationship, and Borkman and Shivanandan interviewed 50 couples who were using NFP and discovered that these couples reported a better understanding of fertility, improved communication, sexual intimacy and spiritual well-being.[7,9] Borkman and Shivanandan, however, questioned whether these positive benefits were due to practicing NFP or to self-selection of NFP by persons with higher levels of those qualities.

Although NFP is thought not to produce any serious psychological side effects, there are some reports of increased marital tension and sexual dissatisfaction among NFP users.[12,13] The negative responses to the use ofNFP are generally thought to be a result of fear over becoming pregnant and to be required abstinence from genital activity.[14] Bardwick indicated that couples would rather ignore a daily responsibility for their fertility and that it is difficult to maintain the sustained motivation required to practice NFP.[14]

In contrast to NFP, the use of artificial contraceptives by couples may relieve anxieties over pregnancy and thus improve sexual relationships. Anxiety and self-esteem are closely related.[15] If couples can lower their anxiety and the fear of pregnancy through the use of artificial contraception then their self-esteem may be enhanced. Herold, Goodwin, and Lero found that women with high self-esteem were more likely to have a positive attitude about birth control and more likely to use contraceptives effectively.[16]

Two previous studies compared couples who use NFP with couples using artificial methods to regulate birthP Tortorici discovered that couples who used a variety of methods of NFP to regulate births had higher levels of self-esteem than couples who used a variety of artificial mehtods.[8] Fehring, Lawrence and Sauvage compared the self-esteem, intimacy and spiritual well-being (SWB) of couples using one method of NFP (i.e., the Creighton Model Ovulation Method) to avoid pregnancy with couples using one method of contraception (i.e., oral contraceptives).[17] They found that the NFP group had higher levels of SWB, self-esteem, and intimacy. The differences may have been a result of selection bias. The current study compares two groups (couples using NFP with couples using contraception) on the same variables, however, the subjects for the two groups, unlike the previous study, were randomly selected and were given in-depth interviews to enrich the results with qualitative data.

Methodology

Sample:

There were a total of 40 couples (80 individuals) in the study. Twenty of the couples were randomly selected from the 350 clients enrolled in the educational services of a NFP clinic from a private University Nursing Center and who met the criteria of having used the Creighton Model Ovulation method for at least a one year period to avoid pregnancy and were currently using NFP. The 350 client population included 77 clients who have stopped using NFP and are now using some form of artificial contraception. The second group of 20 couples were randomly selected from these 77 clients and from the clients of a NFP Center located in the Western United States. These subjects had used NFP in the past and then switched to some form of artificial contraception for at least a one year period and were currently using artificial contraception. Eight of the couples in the contraceptive group were currently using oral contraception, six were using condoms, two were using the diaphragm, two were using the contraceptive sponge, and two had been sterilized. Twenty potential couples in the contraceptive group refused to participate when contacted either because of no time or not interested. There were five in the NFP group who did choose to not participate for the same reasons.

The average age of the NFP group was 30.44 years and average age of the contraceptive group was 35.10 years. Seventy-eight percent of the NFP group were Catholic, 12% Protestant, and 10% were listed as other. In contrast, 58% of the contraceptive group was Catholic, 20% were Protestant, and 22% were listed as other. The contraceptive group on a whole had more children (an average of 1.3 children vs. 0.82) and were married for a longer period of time (7.8 years vs. 5.2).

Procedure

Each couple was contacted over the phone by the researcher and if they agreed to participate they were given an appointment to be interviewed either by a research assistant or a nurse certified as a NFP practitioner. The interviews took place in the couple's home or the NFP clinic. (Eleven of the contraceptive couples were not interviewed in person but completed open-ended questionnaires sent through the mail). At the appointment the couples received written and oral explanations of the study and signed a consent form. Subjects were also informed of their right to withdraw and how confidentiality was maintained.

At the interviews the couples (both the husband and wife) were asked to respond separately to the following open-ended statements: 1) Describe how your method of family planning has affected your intimacy with your spouse, 2) describe how your method of family planning has affected your self-esteem, and 3) describe how your method of family planning has affected your spiritual well-being. The last statement had two parts; how has your method of family planning affected your relationship with God, and how has your method of family planning affected your meaning and purpose in life. The interviews were tape recorded and lasted from 112 to one hour in length. After the interviews the couples were given three questionnaires to complete, a self-esteem inventory, a SWB inventory and an intimacy questionnaire. Husbands and wives were asked to independently complete the forms in the order mentioned above. All of the NFP couples completed the tools in the presence of the research assistant. All but 11 of the contraceptive couples completed the questionnaires in front of the research assistants. These couples completed the tools which they received and returned through the mail.

Instruments:

Self-esteem was measured by use of the Coopersmith Self-Esteem Inventory (SEI) (1986). The SEI is a 25-item scale designed to measure evaluative attitudes toward the self in social, academic, family, and personal areas of experience. Test-retest reliability coefficients for the SEI range from .80 and .85.[18,19] Internal consistency has been reported to be 0.74 for males and 0.71 for females. [18] Evidence for construct, concurrent, and predicitive validity has been demonstrated in a number of studies.[15,20]

Spiritual well-being was measured by the Spiritual Well-Being (SWB) Index developed by Paloutzian and Ellison.21 The SWB index is 20-item self-report tool with two sub-scales; religious well-being (RWB) and existential well-being (EWB). The R WB scale reflects the relationship a person has with God (the vertical dimension) and the EWB scale reflects a person's satisfaction with self and meaning and purpose in life (the honwntal dimension). All items are rated on a six-point Likert type scale. Paloutzian and Ellison reported test-retest reliability coefficients of .93 for SWB, .96 for RWB, and .86 for EWB. Coefficients of Alpha reflected internal consistencies of .89 for SWB, .87 for RWB, and .78 for EWB.[21]

Intimacy was measured by the Personal Assessment of Intimacy in Relationships (PAm) developed by Schaefer and Olson.22 The PAm is a 36-item scale that compares the partner's scores of both perceived and expected intimacy. Only the perceived intimacy scores were calculated for this study. The PAm is composed of five subscales (Emotional, Social, Sexual, Intellectual, and Recreational intimacy) and a Conventionality scale. The six items under each subscale were chosen on the basis of factor and item analysis. Reliability testing consisted of a split-half method of analysis. Cronbach's alpha reliability coefficients of the six subscales were at least .70.[22]

Data Analysis

The taped interviews were transcribed verbatim by a secretary. Each interview was then analyzed separately for common themes and responses. Units of analysis were sentences and phrases. To insure validity and to provide further analysis, each interview was analyzed by a panel of three persons, two graduate research assistants and the principal investigator. The themes and groupings were accepted only when the two graduate student research assistants and the principal investigator concurred. Student t-tests were calculated to determine if there were differences in mean scores between the two groups on all scales and sub-scales of the questionnaires.

Qualitative Results

Intimacy: The most common categories of positive responses from the NFP couples as to how NFP affected intimacy with their spouse were: Fertility Awareness/Understanding, Increased Communication, Increased Intimacy Options, and Shared Responsibility. The most common negative responses were: Decreased Spontaneity, Frustrations with Abstinence and Frustrations with Method.

The most common categories of positive responses from the contraceptive group were: Decreased Tension/ Anxiety/Fear/Worry, Increased Spontaneity, Increased Confidence, and No Effect/No Comment. The most common negative responses were: Health Risks, Decreased Enthusiasm and Lack of Spontaneity.

Self-esteem: The most common themes of how NFP affected the self-esteem of the NFP couples were as follows: Increased Self-Control, Increased Control Over Fertility, Increased Self-Confidence, Increased Body Awareness, and Healthy Option/Natural. Negative effects reported were: Decreased Control and Powerlessness.

For the contraceptive group the most common themes for the effect on selfesteem were: Increased Control, Satisfaction in Planning Parenthood and No Effect.

Spiritual Well-being: The most common themes on how NFP affected SWB among the NFP couples were: Enhanced Relationship with God, Increased Faith In God's Will/Trust In God, Appreciation of God's Gifts, Satisfaction with Complying with Church Teaching and Satisfaction with Control over planning parenthood. There were no negative comments other than no comment or no effect.

The most common themes for how their method of family planning affected the SWB of the contraceptive couples were: No Affect, Decreased or No Relationship with God, Being Responsible, Not Complying with Church/God's Intention, Struggle with Church teaching and Increased Control over planning parenthood leads to satisfaction with life.

Quantitative Results

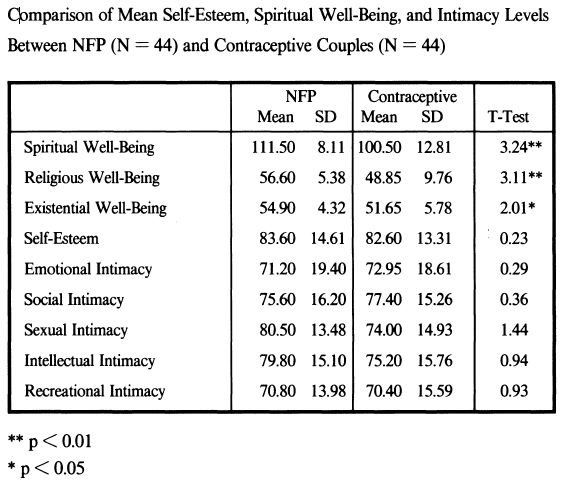

The t-test results indicate that there were no significant differences between the NFP and artificial contraceptive couples in self-rated Self-Esteem and Intimacy scores (See Table 1). However, the NFP couples had statistically higher, spiritual well-being, religious well-being, and existential well-being. Comparison of the variables by gender showed that the NFP males had significantly higher spiritual well-being scores (t = 1.99, P < 0.05) and religious well-being scores (t = 2.06, p< 0.05), but not significantly different existential well-being scores. NFP females had significantly higher spiritual well-being scores (t = 3.24, P < 0.01), religious well-being scores (t = 3.11, P < 0.01), and existential well-being scores (t = 2.01, P < 0.05).

Table 1

Discussion

Intimacy

Although there were no quantitative differences in intimacy between the two groups of couples there were qualitative differences of note. The NFP couples commonly felt that their intimacy was increased by the dynamics of using NFP. One of the most common ways of this happening was through fertility awareness. NFP helped couples learn more about their fertility, their spouse's fertility and this led to an increased understanding of the spouse. An example response to illustrate the dynamics of fertility awareness that leads to a greater understanding of the spouse is from one of the husbands:

I am being a part of her cycle. I understand her period's coming up and I can accept her for that. It's helped me out a lot, to understand where she's at in life and I just feel a lot closer.

Increased communication that resulted in a shared responsibility was another common dynamic. Couples felt that NFP not only aided in their communication and that greater communication enhanced their intimacy but that the increased communication led to a greater shared responsibility. One of the wives stated the dynamics in this way:

I think it's helped with communication a lot. I'm very happy with the fact that he's more involved with the decision that we're making at this point in time of not having children, or not getting pregnant at this point in time.

And a husband stated, "It forced us to communicate more."

The negative aspects of using NFP expressed by the couples (in relation to intimacy) were frustrations with method, frustrations with abstinence and a lack of spontaneity. The negative aspects, however, were not common experiences. An example of each of the negative aspects was as follows:

Frustrations with method: "It is discouraging to have it not work, and not being able to read the signs of the ovulation method. It's difficult when it doesn't work."

Frustrations with abstinence: "When it's too much abstinence, then I think we are not very close. Then you get so upset and you - you don't know what to do."

Lack of spontaneity: "It doesn't lend itself very well to spontaneity."

Most of the NFP couples did not report frustrations with abstinence or lack of spontaneity but rather felt that NFP helped them to be more intimate and to develop behaviors that increased intimacy. Increased intimacy options were a very common response as reflected in this statement:

On the so-called baby stamp nights we tend to choose other methods of intimacy like hugging and you know, just laying together. I guess it's caused us to do other forms of love-making. Caused us to be more intimate.

The contraceptive couples commonly expressed that their method of contraception helped them to be more intimate by allowing them to not worry about pregnancy and to be more relaxed. Contraception has helped them to experience less fear, anxiety, and tension. One woman expressed it this way:

We are more relaxed with one another, more playful. The fear of another unplanned pregnancy has diminished considerably.

The decrease in tension and worry was also due to an increase in confidence that a number of the couples reported. For example:

We feel pretty confident with it. It has maybe alleviated some concern about maybe an unwanted pregnancy at this time.

Some of the couples reported that they had more freedom and more spontaneity in their relationship.

It takes away a lot of the work and a lot of the stress and increased spontaneity.

But other couples, especially those who were using barriers methods felt that they had a decrease in spontaneity and enthusiasm.

You've got to stop and open up the condom so you just kind of, abruptly stop and then try to get close again. - and - It kind of makes me lose my enthusiasm ... I don't really like using a condom.

Although one or two of the couples felt a fear of health risks, the most common comment was "no effect."

Self-Esteem

The dynamics of how NFP affected self-esteem with the NFP couples differed somewhat between the husband and wife. The women overwhelmingly reported a strong sense of increased self-esteem due to a greater understanding of their body, an appreciation of their fertility, a feeling of being more natural and having control of achieving or avoiding pregnancy. Like the wives, the husbands felt a sense of control of when to have or not have a pregnancy but also a sense of self-control over their sexual drives. They also expressed a greater understanding of their spouse's fertility and an appreciation of decreased health risks for them. Only one of the wives reported that NFP had "no effect" on their self-esteem as opposed to about one half of the husbands.

Examples of responses from the wives reflecting body awareness/appreciation, control and a healthy option are as follows:

- It's put me back in contact with my body. Now I welcome my menses in a way I have never done since I got my first period when I was 13.

- It has increased my self-esteem. I've learned more about myself as a woman since I've started ... I just feel better about it on the whole, my self-esteern.1t caused m~ to have more control.

- I have more responsibility and I'm taking care of myself more and I'm learning something about myself. And I think it's improved my self-esteem a lot in that area. And the husbands:

- It has helped me understand my wife's position better.

- I feel more involved, more important, in the relationship. I feel a lot better about having that choice. It's either a fertile day or a non-fertile day and either we are going to get pregnant or we aren't. It really feels good to know that.

The most common response for the contractive group on self-esteem by both the husbands and wives was "no effect" or "no change." For example one husband said, "I don't think it's made any type of difference on my self-esteem." Some of the contraceptive women, however, felt that they had an increased sense of control. This sense of control was expressed by two women as follows:

- Being on the pill makes you feel more in control of the situations. That kind of helps with your self-esteem. You can predict kind of what's happening.

- I feel in control. It's something that I made the decision. A couple of the husbands did report a sense of loss for no longer being on NFP.

- It was kinda nice being on NFP, knowing that we weren't taking any medication.

- I feel good about myself when using NFP but feel temble when using artificial.

Spiritual Well-Being

From a qualitative standpoint, there is a clear difference between the NFP and contraceptive couples in how their method of family planning affected their spiritual well-being; that is, their relationship with God and their meaning and purpose in life. The NFP couples, for the most part, felt that NFP enhanced their relationship with God whereas the contraceptive couples felt that either there was "no effect" on their relationship with God or that there was a decreased relationship. A few of the contraceptive couples described their struggle with their decision to use contraception. Both the NFP couples and the contraceptive couples felt that their method of family planning enhanced their meaning and purpose in life by providing them with increased control over their family planning decisions.

The NFP couples commonly expressed that NFP helped them to have an increased trust in God, an increased faith in God's will, and a greater appreciation of God's gifts. They felt that complying with Church teaching gave them peace of mind, which in turn enhanced their relationship with God. The following statements illustrate some of these dynamics:

Comments from two husbands:

- It's brought God into the picture. My relationship with God has gotten much closer.

- I noticed with this method it's really got us a lot closer in those other areas. I think that's the way God wants men and women to live.

Comments from two wives:

- It's made me fulfill my spirituality. I also feel at peace with the Lord. I guess I look at it from a trust perspective in kinda just putting it in God's hands.

- I feel good about it because it kind of allows me to try and comply completely with Catholic teachings and I'm not putting that obstacle between myself and my relationship with God. The following comments from the contraceptive couples reflect how their method of family planning had no effect or a decrease in the relationship with God.

Comments from two wives:

- I'm less likely to think of God as an integral part of our lovemaking. I seem less open to how he calls me to live.

- I don't think for me its really done anything. I consider myself spiritual, but don't consider like the whole sexual intimacy is associated with God.

Comments from two husbands:

- I'm uneasy using artificial 'cause I don't think God approves it.

- At first before I was concerned about sin. I reconciled this as not a selfIsh act but one of family survival.

The difference in SWB between the NFP and contraceptive couples is also supported by the quantitative data. Although most of the NFP couples felt that NFP enhanced their SWB the differences between the two groups could be due to the possibility that the less spiritually oriented couples were more likely to drop using NFP and switch to another method.

The qualitative themes for the NFP couples are similar to past studies. For example, McCusker found with 98 couples who used NFP, that they felt NFP increased communication, body awareness, confidence, self-control, shared responsibility and peace of mind.[7] All of these were found in the current study. Borkman and Shivanandan interviewed 50 users of NFP and found increased communication, fertility awareness, increased intimacy, and increased spiritual well-being as common themes.[9] Again, these are all concepts found in this current study.

The quantitative results of this study are somewhat similar to past studies on the same variables. The Fehring, et al, study also compared NFP with contraceptive couples. In this study there were differences in SWB between the two groups but also self-esteem and intimacy.[17] The differences might be due to the fact that the couples in the Fehring, et aI, study were not randomly selected and that all of the contraceptive couples used oral contraceptives. Tortorici also found that couples who used various methods ofNFP had significantly higher self-esteem than couples who used various methods of contraception.[8] The present study did not find differences in self-esteem between the two groups.

In conclusion, the findings of this study indicate that the NFP couples in this study felt that their method of family planning helped them to gain a greater fertility awareness, increased communication, provided self-control and confidence, a shared responsibility, enhanced their relationship with God and provided them with more ways of expressing their intimacy. Some of the NFP couples felt frustrations with abstinence and the use of the method, and a decrease in spontaneity. Overall, there was a sense that although living with their fertility was a challenge, they sensed that their fertility was integrated into their lives. The contraceptive couples on the other hand felt that their methods of family planning helped to decrease their worry over pregnancy, increase control and confidence over family planning, and decrease their relationship with God. Many of the contraceptive couples felt that their method of family planning had no effect on their relationship with God or each other. There was not a sense that their fertility was integrated into their lives. The quantitative findings showed that the NFP couples had significantly higher levels of SWB than the contraceptive couples. These differences may not be due to the method of family planning but rather to attribute variables. For example, the NFP couples may have been more spiritual and religious than the contraceptive couples, even before they began using NFP.

The chief implication from this study is that health professionals who work with couples using methods of NFP should monitor their clients for level of frustration over abstinence and lack of spontaneity in order to help them cope with these frustrations. This may be accomplished by emphasizing the positive aspects ofNFP, such as increased fertility awareness, improved communication, and the opportunity for enhanced initimacy through means other than genital expressions. Couples may also be reminded that many couples experience a period of adjustment with the use of NFP. Another implication is that health professionals might counsel contraceptive couples that although they might have less anxiety over pregnancy and a feeling of increased control they might also experience a lack of peace over their spirituality and a decreased sense of spiritual well-being.

The findings of this study must be interpreted with a great deal of caution. The results apply only to the couples in this study. Further research is needed to validate the themes with other populations of couples using various methods of family planning. Longitudinal studies are recommended in order to determine if NFP causes changes in couples' intimacy, SWB, and self-esteem. Researchers could measure these variables when couples initiate the use of NFP and at various future time intervals, for example at six months, one year, and two years. Finally, researchers need to develop measurement tools for intimacy and sexuality that more closely capture the conceptualizations of these phenomenon within the context of NFP. Some of the themes and concepts found in this and previous studies could be used as the basis for these tools.

References:

- [1] Ory H, Forrest J, Lincoln R. Making Choices Evaluating the Health Risks and Benefits of Birth Control Methods. The Alan Guttmacher Institute, New York, 1983.

- [2] NAACOG, Contraceptive Options. OGN Nursing Practice Resource. The Nurses' Association of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (l99l1September),1-20.

- [3] Marshall J, Rowe B. Psychological Aspects of the Basal Body Temperature Method of Regulating Births. Fenility and Sterility 1970;21(1):14-19.

- [4] Billings 1. Natural Family Planning: The Ovulation Method. The Liturgical Press Collegeville, MN,1972.

- [5] Billings E, Billings 11, Brown JB, Burger H. Symptoms and Hormonal Changes Accompanying Ovulation. Lancet 1972;1:282.

- [6] Hilgers T, Daily D, Hilgers S, Prebil A. The Ovulation Method of Natural Family Planning: A Standardized Case Management Approach to Teach (Book One). Creighton University Natural Family Planning Education and Research Center, Omaha, NE, 1982.

- [7] McCusker MP. Natural Family Planning and the Marital Relationship: The Catholic University of America Study. International Review of Natural Family Planning 1977;1:331-340.

- [8] Tortorici, J. Conception Regulation, Self-esteem, and Marital Satisfaction Among Catholic Couples: Michigan State University Study. International Review of Natural Family Planning 1979;3:191-205.

- [9] Barkman, T, Shivanandan M. The Impact of Natural Family Planning on Selected Aspects of the Couples Relationship. International Review of Natural Family Planning 1984;8(4):58-66.

- [10] Ball M. Integration of Abstinence in NFP. International Review of Natural Family Planning 1987;11:34-39.

- [11] Aguilar, N. The New No-pill No-risk Binh Control, Rawson Associates, New York, 1986.

- [12] Liskin, LS, Fox G. Periodic abstinence: How Well Do New Approaches Work? Population Reports Series 11981;3:33-71.

- [13] Bledin KD Psychological Aspects of Family Planning. Midwife Health Visitor & Community Nurse 1982;18:518-523.

- [14] Bardwick 1M Psychodynamics of Contraception With Particular References to Rhythm. In Wa Urricchio & MK Williams (eds.), Proceedings of a Research Conference on Natural Family Planning (pp. 195-207). The Human Life Foundation. Washington, DC, 1973.

- [15] Coopersmith, S. Self-esteem Inventories. Consulting Psychologist Press Inc. Palo Alto, CA, 1986.

- [16] Herold ES, Goodwin MS, Lero DS. Self-esteem, Locus of Control, and Adolescent Contraception. Journal of Psychology 1979;101:83-88.

- [17] Fehring R, Lawrence D, Sauvage C. Self-esteem, Spiritual Well-being, and Intimacy: A Comparison Among Couples Using NFP and Oral Contraceptives. International Review of Natural Family Planning 1989;13(3/4):227-236.

- [18] Bedeilan AG, Geagud RJ, Zmud H. Test-retest Reliability and Internal Consistency of the Short Form of Coopersmith's Self-esteem Inventory. Psychology Reports 1977;41:1041-1042.

- [19] Frerichs M. Relationship of Self-esteem and Internal-external Control to Selected Characteristics of Associate Degree Nursing Students. Nursing Research 1973;22:350-352.

- [20] Kokenes B. A Factor Analytic Study of the Coopersmith Self-esteem Inventory. Adolescence 1978;13:149-155.

- [21] Paloutzian R, Ellison C. Loneliness, Spiritual Well-being and Quality of Life. In L Peplau & D Perlman (Eds.). Loneliness: A Source Book of Current Theory, Research and Therapy (pp. 224-237). John Wiley and Sons, New York, 1982.

- [22] Schaefer MT, Olson D. Assessing Initmacy: The PAIR Inventory. Journol of Marital and Family Therapy 1981;7:47-60.

Article copyrights are held solely by author.

[ Japan-Lifeissues.net ] [ OMI Japan/Korea ]