Anthropological Differences between Contraception and Natural Family Planning

Almost twenty years ago, Pope John Paul II in his apostolic exhortation Familiaris Consortio called on scholars to study the anthropological and moral differences between the recourse to the natural rhythms of a woman's menstrual cycle (i.e., natural family planning) and contraception1. Although natural family planning (NFP) and contraception can both be used to prevent pregnancy, there are conspicuous differences between use of natural methods and contraception. Most people, however, have difficulty in distinguishing what the differences are and in understanding why some religious groups, health professionals, and other members of society consider contraception (but not natural family planning) immoral or problematic. As the title indicates, our focus will be more on anthropological than on moral differences. That is, we do not explicitly address the question, "What is the core criterion for judging the moral rightness or wrongness of contraception?" Nevertheless, our findings on the consequences of contraception and sterilization are quite relevant for moral judgments, even for those who use a consequentialist or proportionalist approach in morals. For example, how moral is it to treat a woman's fertility/ reproductive system as a disease or to alter or destroy it?

Discussing anthropological differences between contraception and natural family planning raises questions not usually asked in comparing what can at first sight simply appear to be two approaches toward the same end (birth control). These questions invite a recontextualization of the entire discussion within much more inclusive concerns for the complete human person, male and female, and their sexual relationship to each other (1). In most areas of personal health, many individuals rightly call for medicinal or surgical approaches to health care that are more holistic and natural and less intrusive, and they also actively support ecological conservation of the world's macro-environment. Yet, there seems to be a puzzling inconsistency when it comes to the very delicate micro-environment, and especially that of the female reproductive system and its care. Respect for the natural environment and preference for fostering natural biological processes in health care (rather than premature or even unnecessary medical or surgical interventions) would be expected to favor natural ways of dealing with human fertility. They would seem to preclude support for the medical, mechanical, or surgical intrusiveness of contraception or sterilization over the natural processes of NFP or fertility awareness.

The almost universal promotion of contraception rather than of fertility awareness is a puzzling anomaly in view of the use of holistic and ecological principles in other health and environmental concerns. An even more inclusive context for interpreting arguments about contraception, especially the arguments in the highly controversial encyclical Humanae Vitae of Pope Paul VI, would place the papal arguments about contraception in the context of the Church's social teachings and her teachings on the authentic development of peoples (for example, in the encyclical Populorum Progressio)2. But space limits us to the more personal and interpersonal rather than the more general social context.

This paper will analyze the two approaches to family planning in order to extrapolate and clarify the differences. Most of its evidence is empirical (supplied chiefly by Nursing Professor Richard Fehring), but it will also include some reflection on the evidence from a faith perspective (with the help of theologian Fr. William Kurz). The first part of the paper will define, compare, and contrast NFP and contraception and will examine some consequences of the use of each. In the second part, research evidence will be presented that compares NFP to contraception on a number of psychological and social variables. The paper ends with a table that summarizes the differences.

I. Definitions

Natural family planning (NFP) is a term that has been in use since about 1970 to refer to methods of monitoring a woman's naturally occurring biological markers of fertility in order to determine the infertile and fertile times of her menstrual cycle3. Knowing whether the woman is in the fertile or infertile stage of her cycle, the woman or couple can then choose to use this information either to achieve or to avoid pregnancy. Abstinence from sexual intercourse or genital contact is practiced during the fertile times if a couple wishes to avoid pregnancy, whereas sexual intercourse is performed during the peak of fertility if they wish to achieve a pregnancy. NFP, therefore, is essentially fertility awareness - learning about and monitoring the fertile and infertile times of a woman's cycle and using that information for self-knowledge, health reasons and family planning purposes.

The biological markers of fertility that are commonly self-monitored during the woman's menstrual cycle in the practice of NFP are the woman's resting body temperature, the changes in the sensations and characteristics of cervical mucus, and the changes in the characteristics of the cervix itself4. At the time of peak fertility, i.e., around the time of ovulation, the resting body temperature rises about .2 to .4 of a degree Fahrenheit; cervical mucus becomes copious, watery, slippery, and stretchy; and the cervix becomes soft, raised, and open. Modern methods of natural family planning use either one or a combination of these signs of fertility. Modern technology has also provided the means by which a woman can objectively self-monitor urinary metabolites of the female reproductive hormones, which signal the fertile time of a woman's cycle. A variety of monitoring devices (from simple stamps, charts, thermometers, and beads, to more sophisticated electronic monitors) can aid the woman in tracking her biological markers of fertility5. When used correctly and consistently, NFP can be a very effective means for either avoiding or achieving pregnancy6,7.

A broader definition of natural family planning includes what is often referred to as the NFP lifestyle, a lifestyle in which men and women learn to live with, understand, and appreciate their fertility [3]. Fertility is fully integrated into their relationship and way of living. This integration of fertility is what provides NFP with its holistic nature. One key to NFP is that it values the integral meaning of sexual intercourse between a man and woman. NFP allows the sexual act to retain its integrity, in that its procreative nature (i.e., the natural fertile potential of the act) remains, along with its unitive or bonding nature. With NFP nothing is done to interfere with fertility or with the reproductive system, an integrated biological organism that is vital for the propagation of humankind. Most individuals who use and teach NFP regard fertility as a special gift that should be protected and cared for. A woman, a man, or a couple who are infertile and wish to have children know too well how precious that gift can be.

Contraception, which is often referred to as birth control, is the prevention of the fertilization of the human ovum. Contraception works either by suppressing, blocking, or destroying fertility8. Unlike natural family planning, which works by understanding and monitoring the reproductive system, contraception (by its very name) takes action against conception and the human reproductive system. The means of contraception include: devices which serve as barriers to the human cells of reproduction (e.g., the male condom or the female diaphragm); chemicals which destroy or incapacitate the human cells of reproduction (e.g., spermicides); chemicals or hormones which suppress ovulation, thicken the cervical mucus, or alter the female reproductive system (e.g., the oral contraceptive pill or injectable female hormones); and the destruction of fertility altogether through surgical sterilization (i.e., tubal ligation or vasectomy). There is also some controversy as to whether certain methods of contraception (e.g., the pill or the IUD) alter the reproductive system in a way that prevents the developing human from implanting in the uterus of the mother9,10. The last mechanism would not properly be considered to be contraception, since conception, the formation of a new individual from union of sperm and ovum, does take place, but rather to be early abortion.

Modern contraceptive methods (like the birth control pill, the IUD, and sterilization) are very effective in helping a woman or a couple prevent pregnancy11. As such, contraception provides women and men control over their reproductive capacity. This control presents the freedom for the woman (or the man or the married couple) to carry out spacing of family or to pursue career, education, and other activities while continuing to remain sexually active. Some contraceptive methods help to decrease the likelihood of a sexually transmitted disease and some have positive health benefits (e.g., oral hormonal contraception may decrease the likelihood of ovarian cancer)12. Most contraception methods are easy to use and harmonize well with career-oriented (in addition to family-centered) lifestyles of today's modern culture. They are widely available: health professionals are trained in and knowledgeable about the various methods of contraception, and they readily prescribe them for family planning and for a host of other health problems.

Even though at times the goals of couples avoiding pregnancy through NFP are similar to those avoiding pregnancy through contraception, the dynamics of their attitudes and relationship to their fertility are quite divergent. Whereas couples who use NFP are trying to understand and live within the framework of their fertility, even earnestly Christian couples who use contraception are making no effort to understand their fertility but are simply trying to avoid its natural consequences while continuing to be sexually active. The ability to continue engaging in intercourse without concern for its possible natural consequences and without periods of required abstinence is surely the most substantial reason for the popularity of contraception over NFP. Whether or not they are conscious of it, the actions of even conscientious couples who are using contraceptives would intimate an option not to live with the natural limits and rhythms of their fertility. In the context of contraception, fertility can often be perceived as an inconvenience unless a couple desires to have a child.

Consequences of Methods of Family Planning

There are significantly different consequences to whether one lives with one's fertility through the use of natural family planning or avoids one's fertility through contraception. These consequences affect individuals, marriage, and society as a whole.

When the more effective forms of modern contraception (especially the pill) became available, many (including feminist scholars, religious leaders, and health professionals) predicted that contraception would be a great benefit to society. Projections were that the pill would free women from the dangers of unwanted pregnancy and childbirth, decrease infant and maternal mortality, provide women with reproductive control, help women to pursue career and educational goals, strengthen marriage and decrease population13,14,15. The need for abortions would also decrease because the babies conceived would be wanted.

Others, however, predicted that the widespread use of contraception would have deleterious effects on women, men, marriage, and society16,17,18. These predicted effects included the lowering of sexual morality, the treatment of women as sexual objects, the loss of sexual self-control, and an increase in divorce. Nor has NFP been immune from criticism and debate. Some have charged that natural methods of family planning are not in fact natural but destructive to marriage and degrading to women19,20. Promoters of NFP counter these charges by citing its positive benefits on individuals, marriage, family, and society21.

One way of determining the consequences of the use of contraception and of NFP is to analyze over a period of time the effects which they have on the health of individuals, families, and society. In the United States the use of contraception and subsequently sterilization has increased dramatically over the last fifty years. In 1955, five years before the first oral contraceptive pill was introduced in the U. S., about 55% of women between the ages of 15 and 44 were using some form of birth control and of these, about 22% were using natural methods (about 54% among Catholic women)22. Only about 6% of these women were sterilized22,23. Today, about 70% of women use some form of contraception, with sterilization being the number one method of family planning in the U.S.24. About 39% of women between the ages of 15 and 44 in the United States use sterilization as their primary method of family planning. Oral contraception is used by about 24% and the natural methods of family planning are used by only about 2-3% of women between the ages of 15 and 44.

What is startling about these statistics is that the United States is gradually becoming a sterile country. Once a woman has 2-3 children and/or reaches the age of 40, the likelihood that sterilization (male or female) is her method of contraception is almost 70%. About another 6% of the sexually active women of that age are using the oral contraceptive pill [24]. These statistics on sterilization plainly imply that Americans have difficulty in living with their fertility. The social impact that temporary or permanent sterility has on this country is yet to be determined.

In general, many of the predicted consequences of the pill, both positive and negative, have been realized. Maternal and infant mortality has dropped considerably in countries where a large percentage of women are using modern forms of contraception. Some of this decrease is the result of women being able to space children at longer intervals so that they are both physically and mentally capable of having and caring for children. However, decreased mortality is also due to better nutrition, medicine, surgery, and access to prenatal health care. So too, women are no longer as limited by motherhood and are now able to pursue education, careers, sports, and entertainment at levels approaching (and in areas such as education exceeding) men. In addition, population growth rates have either leveled off or decreased in modern industrialized countries.

Many of the social indicators in the past half-century have been more obviously negative. Since the 1950s and the introduction of modern methods of contraception, especially the pill, there has been a considerable increase in divorce, sexually transmitted disease, abortion, cohabitation, and out-of-wedlock births. In the 1950s the divorce rate was around 10 per 1,000 married women; by the 1980s this rate doubled to around 20 per 1,000 women25. Today, almost half of all marriages end in divorce. In the 1950s there were only about five basic types of STDs identified by health professionals; now there are over twenty. Some of these are incurable, can precipitate cancer, or cause infertility. Others (like HIV) can cause serious illness, debilitation, and the likelihood of a short life. There are estimates that one in four individuals in the United States between 13 and 45 have some type of STD26.

The forecast that the more every child is a wanted child, the fewer abortions there would be, has been conclusively shown to be false. Not only has widespread use of contraception not decreased abortion; on the contrary, the numbers of abortions have increased dramatically. Most years since 1974 there have been some 1.5 million abortions per year. Approximately 339 abortions are performed for every 1,000 live births in the U.S., and about 24% of U.S. females of reproductive age have had an abortion27. According to researchers at the Center for Disease Control and Prevention in Atlanta, induced abortions are usually linked to unintended pregnancy, which often occurs despite the use of contraception [27]. Researchers at the Alan Guttmacher Institute indicate that half of all women having abortions state that they have used some contraceptive in the month they became pregnant28. Of those who did not use contraceptives in that month, most have used contraceptives in the past. Only 9% of abortion patients have never used contraception to prevent pregnancy [28]. Clearly, abortion is being perceived and used as a backup to failed contraception.

Another anticipated benefit of the pill was a sharp decrease in outof- wedlock births. The actual statistics show the opposite trend: in the U.S., among adolescents and young adults, half of all babies are born to unwed mothers. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, 1.29 million babies were born to single women in 1998. The rate of outof- wedlock births to women under the age of twenty is around 70%, whereas in 1950 (before the pill) the figure was less than 10%29.

An additional failed prediction was that the pill would lessen child abuse. Rather, statistics reveal the opposite - dramatically increased incidences of child abuse, though not by married couples. The likely occasions for such child abuse correlate closely to the lack of chaste lifestyles and of normal healthy marriages. Fatal child abuse among families with natural two-parent structures is rare, around 2-3%; the rate increases exponentially to almost 70% among unmarried mothers who cohabit with boyfriends. The absence of normal families also affects children negatively in other predictable ways, as seen in its obvious negative correlation to children living in poverty. Single-parent households have yearly income levels far below those with two-parent families. A senior fellow in Family and Cultural Issues at the Heritage Foundation, Patrick Fagen, stated that the trend of out-of-wedlock births, aggravated by divorces which leave children without a married mother and father living at home, has resulted in a steady increase in the number of children in broken homes. As a result, there has been a corresponding increase in the child's risk of physical health problems, physical or sexual abuse, warped social development, lowered job attainment, lower educational achievement, and more involvement in crime [16].

These statistics illustrate some of the disturbing trends in our society which are related either to the ways contraception has affected sexual behavior and marriages or to the assumptions (facilitated by reliable contraception) that sexual activity need not be confined to marriage, that sexual activity not only can but should be separated from reproduction, and that a child accidentally conceived under these assumptions can be aborted. This is obviously not a claim that all of society's ills (divorce, abortion, child abuse, etc.) are occasioned by contraception; certainly there are other factors involved. However, it is hard to deny that the advent and use of contraception has contributed significantly to these trends. Francis Fukuyama, a noted sociologist and writer for Atlantic Monthly, recently analyzed the major trends in society and listed contraception and the separation of sexual activity from reproduction as one of the key social movements in the past century30. His conclusion is arresting: "If the effect of birth control is to reduce the number of unwanted pregnancies, it is hard to explain why its advent should have been accompanied by an explosion of illegitimacy and a rise in the abortion rate, or why the use of birth control is positively correlated with illegitimacy" across the developed countries of the world.

Consequences of Natural Family Planning

In the 1950s there were approximately 20,000,000 couples in the U.S. using some form of NFP, whether it was rhythm, basal body temperature (BBT), or prolonged abstinence [23]. Today, only about 150,000 couples in the United States use modern methods of natural family planning [24]. In the 1960s when the sexual revolution was at its height, there were a number of groups that proclaimed (and non-scientific studies that suggested) that the practice of NFP was ineffective and harmful to marriage. In fact, one of these studies was instrumental in convincing a papal birth control commission, which was investigating the question of birth control and the pill, to recommend in 1967 that Catholic Church teaching on birth control be changed31. In 1970 the first scientific study on the psychological aspects of NFP was published. The study involved British couples who were currently using some form of BBT as a form of family planning. The author of this study, Dr. John Marshall, found that over 75% of the couples using BBT felt that it was helpful to their marriage32. However, about 42% of the couples also noted some psychological difficulties in not being able to handle abstinence and perceived a lack of sexual spontaneity. Since then a number of small studies have been published that have been consistent in reporting that from 78% to 85% of the couples who use NFP indicate that NFP has helped strengthen their marriage. It did this by providing them with a greater understanding of their combined fertility, by increasing their level of communication, by helping them to develop self-control and trust for their partner, by enhancing their intimacy and increasing their sexual libido, and by facilitating their relationship with God33,34,35,36.

However, these studies were also consistent in showing that a significant minority of couples who use NFP experience difficulties. Couples who use NFP often report that they struggle with periodic abstinence, that they are unable to be spontaneous in their physical sexual expression, that they fear getting pregnant, or that they experience difficulties in the daily monitoring of their signs of fertility. Other complaints about NFP are that couples feel that sex is on a schedule and that the woman has a heightened desire during the fertile time and a lack of desire during the post-ovulatory phase [20]. To our knowledge, there only have been two small (non-scientific) studies on divorce rates among couples who use NFP. Both studies indicate that the divorce rate among NFP couples is very low, around 2-5 per 1,000 couples37,38, which is quite a difference from the current statistic of 20 divorces per 1,000 couples in the U.S.

The problem with these psychological and divorce rate studies on NFP is that they are few in number, are based on a small number of couple respondents, and are non-comparative in design. For example, the low divorce rate among NFP couples could be a result of self-selection - that only couples who have strong relationships or marriages choose to use NFP. More studies need to be conducted on the psychological dynamics among couples who use NFP in comparison with couples who use contraception.

II. Research on Comparisons Between Contraception and NFP

Research comparing contraception and NFP is sparse. In 1979 a doctoral student at Michigan State University, Father Joseph Totorici, O.P., reported a small study that compared the self-esteem of married couples then using NFP with married couples using contraception39. He found that as a rule the Catholic couples using NFP scored significantly higher on self-esteem than those couples who used contraceptives or no method. His sample was small (15 NFP couples vs. 30 contraceptive couples). Twelve of the 15 NFP couples were selected by convenience. The reason why there were so few NFP couples in his study and why they were not randomly selected from the same population as the couples on contraception (i.e., couples enrolled in Roman Catholic parishes) was that there were so few couples using NFP.

The first author of this paper conducted two studies which compared married couples who were currently using some form of contraception (and had been for at least one year prior to the study) with married couples currently using some form of NFP (for at least one year prior to the study)40,41. The variables of self-esteem, intimacy, and spiritual well-being were compared between the two groups. Each study had 22 NFP couples and 22 contraceptive couples. Both studies found that the NFP couples had higher levels of spiritual well-being, but owing to the small number of participants there was not enough statistical power to detect other significant differences among key variables.

In order to increase the power to detect statistical differences, this paper reports the combined analysis of the respondents from both studies. We were able to combine the analysis since both studies had the same dependent variables, i.e., spiritual well-being, self-esteem, and intimacy. Self-esteem was measured by the Coopersmith's Self Esteem Inventory43,44, intimacy was measured by the Personal Assessment of Intimacy in Relationships (PAIR) developed by Shaefer and Olsen45, and the Spiritual Well Being Index was developed by Ellison and Paloutzien46. All three measures have reported scientific evidence for their validity and reliability. Descriptions of this evidence can be found in the cited references and in the first author's two published studies [40,41].

As shown in Table 1, the combined studies yielded 44 couples or 88 individuals for both the NFP group and the contraceptive group. The average age and number of children for the 44 NFP couples was 30.6 and 1.7 respectively and that of the 44 contraceptive couples 32.3 and 1.5; 80% of the NFP couples and 57.5% of the contraceptive couples were listed as Catholic, 7.5% of the NFP couples and 22.5% of the contraceptive couples were categorized as Protestant, while 11.5% of the NFP group compared with 20% of the contraceptive group were listed in the religious category as "other."

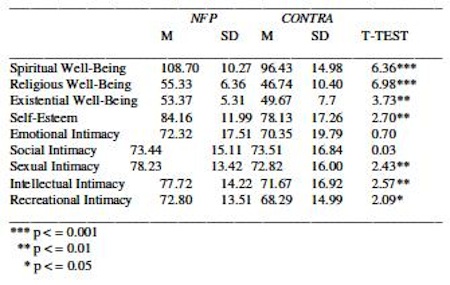

TABLE ONE: A Comparison of Psychological /Spiritual Variables between NFP Couples (N=44 Couples & 88 Individuals) and Contraceptive Couples (N=44 Couples & 88 Individuals)

The results show that the NFP couples have statistically higher levels of spiritual well-being (both religious and existential), higher levels of self-esteem, and higher levels of intellectual, recreational, and sexual intimacy. These findings were also verified through open-ended interviews in which each respondent couple participated. Although the subjects of these two studies were either matched (on income and education) or randomly selected from the same pool of couples, the findings could result from the fact that couples in stronger relationships choose to use NFP rather than from NFP strengthening the relationship. There could also be religious, cultural, economic, and other factors that influenced the differences. A study that examined changes across time among users of NFP in comparison to users of contraception (rather than at one period in time) would provide more convincing evidence.

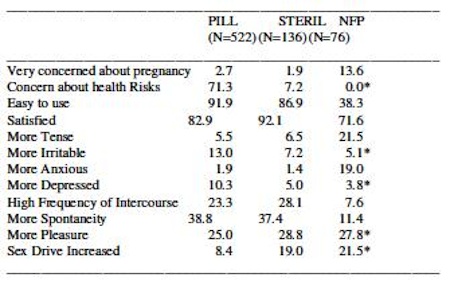

Dr. Bjorn Oddens, M.D. (from the International Health Foundation, Geneva, Switzerland) recently reported a study in which she surveyed 1,466 German woman (during the months of March and April, 1995) on the physical and psychological effects of their past and current use of five common methods of family planning, i.e., oral contraception, condoms, IUD, NFP, and sterilization [46]. Of these respondents 1,303 had past or current use of oral contraceptives, 996 had used condoms, 428 had used NFP, 342 had employed intrauterine devices (IUD), and 139 were sterilized. The results showed that women had the most satisfaction with sterilization, followed by use of the pill, and the least with condoms and NFP. That 21.5% NFP users were "more tense" (compared to 5.5 of those sterilized and to 1.9% of those on the pill) and that 19.0% of NFP users were "more anxious" (compared to 1.9 and 1.4%) also raises significant concerns for further investigation. Still and all, NFP scored as good or better in 5 of the 12 indicators in the Oddens study. Women currently using some form of NFP had fewer health concerns, were less irritable, less depressed, had high levels of sexual pleasure and a higher sex drive than with other methods of contraception (See Table 2).

Without denying the negative indications about NFP raised by the Oddens survey, it is not unfair to point out that the questions asked in that survey were more adapted to the dynamics of contraception than those of NFP. For example, there were no questions on whether the method of family planning increased understanding of fertility, selfcontrol, communication, trust, intimacy, or relationship with God. Theoretically one would expect NFP to do better than contraception on these indicators because of its dynamics of living with one's fertility rather than avoiding it. However, research would be needed to verify whether this is so.

TABLE TWO: Satisfaction with Current Use of NFP In Comparison with Current Users of Contraception and Sterilization (In Percentages)

Dynamics of NFP Versus Contraception

An interesting study was recently published in the journal Social Science and Medicine in which focus groups of unmarried men and women discussed the use of contraception and the effects on their relationships47. The theme that resulted from the focus groups was that an effective contraceptive (like the pill) should be used in a relationship to prevent pregnancy, but so too should a barrier like the condom in order to prevent the transmission of sexually transmitted diseases. Known as dual contraception, this is a standard recommendation among health professionals for persons having sexual relationships outside of marriage. The consensus from the groups was that dual contraception use was necessary and responsible in a relationship. What also emerged from the groups, however, was that, although they knew that they should be using dual contraception, the use of a condom signaled to the sexual partner a lack of trust or perhaps even infidelity. There was no discussion among the participants about the appropriateness of sexual intercourse only in marriage, the practice of chastity, or being faithful.

These discussions on methods of birth control evidently assume that sexual intercourse is appropriate outside of marriage and that one's only concerns should be to prevent pregnancy and STDs. They do not treat the dynamics on how methods of "safe sex" affect relationships. Most relationships benefit from understanding, trust, respect, communication, self-control, generosity, and love. These discussions fail to ask which methods of birth control better promote these characteristics, although outside the context of marriage there would naturally be little consideration of NFP.

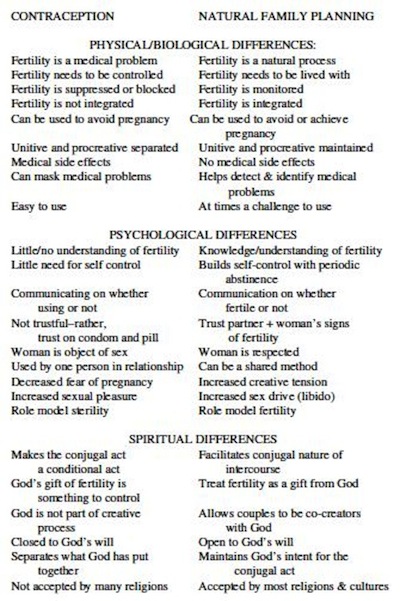

In an attempt to analyze succinctly the differences that NFP versus contraception has on self and on relationship with others and with God, this article's first author developed a table that summarizes the differences in short phrases. The phrases were taken from a number of sources, including the literature on contraception and on NFP and interviews that the author conducted with NFP and contraceptive couples [40,41]. The table was also placed on an Internet NFP discussion list (one that includes around 300 experts in NFP and related fields) in order to receive feedback and modification. The final version (Table 3) resulting from this feedback process uses a framework that categorizes physical/biological, psychological, and spiritual dynamics. The intent of the table is not to say the final word on the differences between NFP and contraception but rather a focus for clarification and discussion.

Under the category of physical/biological dynamics, the table illustrates that contraception treats fertility as a medical problem (i.e., as a disease) and as something that needs to be controlled. Because contraception works by suppressing or blocking fertility, it is not an integrated system. The mechanisms that block or suppress fertility often cause side-effects or mask underlying medical problems. Although, for the most part, they are easy to use, the side-effects often prompt discontinuation. In contrast, natural family planning treats fertility as a natural process, works by monitoring and understanding natural fertility signals, and is an integrated system that can be used both to achieve and to avoid pregnancy. Although NFP takes some time to learn, and at times can be a challenge to use, it has no medical side-effects. The greatest difference in this category is that NFP, unlike contraception, does not of its nature separate the unitive and procreative purpose of the sexual act.

TABLE THREE: NFP vs. Contraception: A Comparison of Marital Dynamics

The psychological and behavioral differences between the use of contraception and the use of natural family planning are considerable. Because contraception is easy to use (e.g., taking a pill once a day or not having to do anything after sterilization) and because it involves blocking, suppressing, or destroying fertility, there is little need either for understanding fertility or for self-control. Furthermore, it requires very little communication between the couple other than to know whether one or both are using some form of contraception. NFP, on the other hand, requires communication between spouses on whether one is fertile or not, on what the couple should do with that information, and, if they are avoiding pregnancy, on how to express their intimacy in other than genital ways.

Of course, in contraceptive marriages also self-control is built in through such factors as respect for differences in sexual desires, attending to one's spouse's sexual or other needs, adjusting to the presence of young children, and the like. Love for one's spouse and children already begins to teach forms of sexual self-control. Still, of itself contraception is based on the general assumption that since technological control is less demanding and less stressful than sexual self-control, it is therefore preferable. As much as feasible in concrete spousal relationships, sexual intercourse and contact should be available whenever desired and should be as spontaneous as possible. NFP, in contrast, works by building in periods of self-control during the time of periodic sexual abstinence.

It seems a self-evident principle that in almost every sphere of human endeavor which is fulfilling, success in that sphere requires a good deal of effort, planning, self-discipline, and the like. In other (but unfashionable) words, few worthwhile human goals can be achieved with only spontaneity and without significant levels of asceticism. An athlete has to exercise self-discipline in diet, in exercise, in strength building, in practice. An artist who uses her body in dancing or ballet or figure skating has to combine practice and diet and discipline to become any good. Becoming a good student requires self-discipline and long scheduled (not necessarily spontaneous) hours of study and practice, as well as abstinence from other activities. Even building human relationships and communities requires a good deal of self-discipline and attention to others, more than self-centered assertion and focus. In all these areas, asceticism is required for significant progress. If sexual relationships in themselves are to be regarded as dignified and worthy human endeavors, especially in the context of building stable, productive, and loving families, one would surely expect some similar need for selfdiscipline and asceticism in order to attain increased intimacy and genuine growth in these sexual and spousal relationships. Otherwise, sexual activity risks being reduced to the level merely of urges, whims, fantasies, "spontaneity" - to merely instinctive behavior or some inferior form of game that does not require practice or self-discipline for growth and improvement. If asceticism is required in virtually any other form of worthwhile human endeavor, the refusal in some contraceptive propaganda to value even the most minimal asceticism with regard to sexual abstinence seems to reduce sexual activity to the level of rudimentary games or unrestrained indulgence of biological urges.

Another unspoken if often-unconscious presupposition of contraception is that, instead of trusting one's sexual partner, one merely makes sure that she is on the pill and that he is using a condom. NFP can only work if there is trust between the partners. The man trusts that the woman is monitoring her fertility signs, and together they trust what information these fertility signs provide. There is also a trust that the man will support and respect the woman's judgment.

Probably one of the most troubling aspects in this psychological/ behavioral category is that with contraception (if one blocks out fertility or sterilizes the act of intercourse), the woman becomes always available (biologically) for intercourse and thus is quite susceptible to becoming an object of sex rather than of love. Although either or both members of the relationship can use contraception, women are more often the ones on whom that responsibility falls. Furthermore, although men are also at risk for being treated as a sex object, in our society that risk appears greater for women, whose sexuality evidently seems more expressly oriented toward procreation and family than men's.

One of the most fascinating dynamics under the psychological/ behavioral category is how contraception and NFP affect human sexuality. As indicated in the above research studies, couples who are on contraception, especially the Pill, the IUD, or sterilization, have decreased their anxiety and fear over a pregnancy, whereas couples using NFP have greater anxiety and tension over the possibility of pregnancy. Although contraceptive couples feel more relaxed in their love making because of the decreased fear of pregnancy, they might be missing the creative tension that NFP couples experience. This creative tension is sometimes described as "the spice of life." In each cycle, NFP couples know their time of fertility. Therefore, they know that at that time they could create new life - an awe-inspiring thought and experience. Without that creative potential, something is missing in the sexual act of intercourse. Contraceptive couples who are permanently or temporarily sterile through contraception also in a sense sterilize their relationship - they have removed its creative potential. Yes, this creative potential can be difficult to live with; it is challenging and at times draining; but nothing can compare with new life to keep older life "alive." Today's contraceptive couples often appear to attempt to replace that spice with cars, sports, vacations, and pets. It is not even that uncommon today to hear an expression previously reserved for pets ("being fixed") applied to one of the spouses.

An incompletely demonstrated dynamic is how contraception affects parents as role models for their children. Although small children are unaware of their parents' contraceptive practices, it is common for college students to talk freely about their parents' form of birth control. In effect, couples on contraception demonstrate to their children that fertility is not a part of their relationship unless they wish it to be. Sexual intercourse is available at their wish and there really is no need to abstain. Children are not given examples of how to be chaste within marriage or of the need to be chaste. Because the procreative dimension has been suppressed or eliminated in a contraceptive marriage, it provides neither awareness nor example of how to live with one's fertility. Even couples in the 1950s who were disappointed with rhythm communicated a sense that fertility was a dynamic in their lives. The NFP examples of chastity, of course, also need to be integrated within a complete set of marital values including reasonable sexual fulfillment. In addition, couples who become voluntarily sterilized convey a premature sense of finality to a family. Generosity toward new life will have to await another generation.

A junior student in a Natural Family Planning class at Marquette University mentioned in a paper that she has no role model on how to live with one's fertility48. She said:

The people of generation X have grown up knowing birth control. By the time they were in their 20's, they had more or less accepted AIDS and along with it condoms as a means of protection. Growing up as children of the baby boomers, this generation as a whole does not have strong feelings about premarital sex or contraception.... We have a generation that lacks a role model in the family, and we need to find new ways to promote the ideology and methods of natural family planning.

The final category of comparison between contraception and NFP is the spiritual. This category is probably one of the most difficult to compare and the most controversial. The differences in this category were essentially taken from experiences that the authors of this paper have had with couples (in clinical and pastoral practice) and from research interviews with many couples using NFP and contraception. A key spiritual difference between the use of contraception and NFP is in the expression of love between a man and woman49. The act of intercourse signifies a totality of giving of oneself to the other; it is an act of abandonment and of complete trust. With contraception, however, this totality of giving is conditional or missing. A contraceptive act of intercourse is conditional in that either the man or the woman (or both) are not willing or able either to give of themselves totally or to receive the other person totally - that is, they are unable to give or receive their fertility. A contraceptive act of intercourse demonstrates a lack of integration of the couple's fertility and a lack of wholeness.

Couples who use contraception usually do not regard fertility as a gift from God, a gift that needs to be protected and cherished. Rather, fertility is regarded as something that is to be controlled on their own terms. When they encounter infertility problems in trying to conceive a child, they are more likely to try to force the issue technologically (pun intended). When couples are using contraception, the creative process, in which God would potentially act, is absent. Many NFP couples, in contrast, view fertility as a gift and regard themselves as being cocreators with God. They also sense that the use of NFP allows them to be open to God's will and to maintain God's intent for the conjugal act. Contraceptive couples, in contrast, commonly do not see their fertility as having anything to do with their relationship with God. Most strikingly, some contraceptive couples actually report that their use of contraception hinders or blocks this relationship [41]. Although only God fully knows this spiritual consequence, it is not inconsequential.

Conclusions and Recommedations

We have attempted in this paper to diagnose differences between contraception and natural family planning. Some of the distinctions are subtle and others quite evident. Pope John Paul II in Familiaris Consortio mentioned that there are irreconcilable differences between the use of contraception and the recourse to the natural, differences that are not inconsequential. If this is true, what might and can be done? The Marquette University student mentioned above recommended that new technology, the computer, e-mail, and the Internet can be ways of teaching NFP and of spreading its benefits to the next generation. These are all good suggestions if increasing the use of NFP actually becomes an imperative for society. Yet, many would challenge whether this matters. Is contraception harming society? If one accepts the anthropological differences between the use of contraception and NFP as described in this paper and summarized in Table 3, one might respond in the positive. At times American society certainly gives the impression of "slouching towards Gomorrah" (as Judge Robert Bork put it in the title of his book). The evidence of the amount of divorce, teen pregnancy, abortions, STDs, child abuse, and disregard towards human life both at its beginning and its end seems to support the case50. Even if the sudden increase in use of contraception in the second half of the twentieth century did not directly cause this slide, it is hard to doubt that it has significantly contributed to it.

What can be done? Contraception is entrenched in today's society. Contraception has become what Archbishop Chaput of Denver calls an addiction51. For example, in one class section, eight of the ten female students were unable to monitor their menstrual cycles because they were on the pill. This anecdotal data correlates with a 1998 statistical study that demonstrated that 78% of Marquette students were sexually active52. At times the situation can seem hopeless. But faith insists that we must persevere in doing what we know is right with hope in God (if not in observed trends) and to continue to work and to contribute towards a culture of life.

Briefly, some general suggestions for promoting natural family planning include chastity programs for youth and their parents, chastity programs which do not include the use of contraception (i.e., dual message programs), and which promote the understanding and valuing of fertility and true chastity. Unmarried couples who are living together need to be informed about studies that demonstrate the damage that cohabitation can do to their relationship and to their capacity to build new and lasting relationships. It is imperative that diocesan and parish marriage preparation programs include advocates and role models for NFP and provide accurate information on NFP as a viable option for couples. Couples need to learn how to live chastely, apart, and with their fertility intact.

Health professionals also need to come to regard and to treat fertility as a positive normal process and to help women, men, and couples to live with and care for their fertility. There is a small but growing number of physicians who have courageously "converted" to the realization that contraception is neither good medical practice nor good health care. Such health professionals need to be encouraged and supported. It is extremely difficult for a physician or nurse not to prescribe contraception, for often, when they refuse to do so, they are treated by colleagues and patients as being difficult and disruptive to the practice setting, and even stigmatized as not being good or ethical practitioners53.

Schools of medicine, nursing, and the health professions need to include courses on NFP, to treat it as a serious subject for discussion and research, and to aid health professionals in the use of NFP. Parish nursing is a natural area for inclusion of NFP in practice. Current health professionals need to be role models for the next generation in how to integrate NFP into their practice and to care holistically for the health of woman, families, and society.

Perhaps paradoxically, the clergy also need to be converted. Up until 1930, all major Christian religions condemned the use of contraception. Has Christianity been strengthened by the use of contraception since? Were almost 2,000 years of condemnation of contraception a mistake? Similar to the small and growing number of physicians, who have converted to the policy of advising only NFP, there is also a small and growing number of clergy who have converted. They are courageous enough to speak out against contraception and to support NFP, even though they realize that most of their congregation is either on the pill or sterilized. There is also a growing number of younger clergy who have seen the damage that contraception can do to society, religion, families, and individuals and who do not carry the encumbrances of dissent from official Catholic teaching. They are becoming dynamic religious spokespersons of the future church.

So also there is a small but growing number of baby-boomer and older individuals who realize the damage that the contraceptive-fueled sexual revolution has done. They are now willing to admit their mistakes and be a "healed" witness to a better way. Many of these members of the "boomer" generation are now in positions of influence and power. They could, if motivated, make significant changes in our school systems, in our courts, and in public policy.

Finally, as was mentioned, our youth need to be reached. The Internet, television, youth groups, prayer groups, and pro-life groups are all means of reaching the youth and teaching them about the beauty and gift of their fertility. At Marquette University, efforts in all of these areas are taking place. The numbers are small, and progress is slow and often frustrating. However, there are always small victories that give hope for further efforts. To end this paper we would like to share one small victory from a statement by a sophomore student who was in a recent NFP course. She wrote a paper in which she investigated and compared a number of electronic high-tech fertility-monitoring devices54:

In today's society, fertility is viewed as a curse. It is suppressed, tricked and shunned. Menstruation and fertility are inconveniences to the modern day woman. Sadly enough, I too possessed these attitudes. I thought that my menstrual cycle was completely chaotic and irregular. I had no idea that my body was working in its own rhythm. Thankfully, through this project, I began to understand and appreciate being a woman. I realize that I possessed a Godgiven gift and that I need to respect it. Fertility became comprehensible and predictable. It was exciting and amazing to actually see the body's fertility cycle. I felt as if I had a new power, a greater worth. Through this project I became more conscientious as to my overall health, too. I began eating better and working out. I felt as though I had gained a greater control and a better participation level in my bodily processes.... I think that it is important to keep in mind that our bodies are our vessels and the more in-tune we are with them, the smoother the sailing.

References:

1 Pope John Paul II, The Role of the Christian Family in the Modern World (Familiaris Consortio) (Boston MA: The Daughters of St. Paul, 1981). [Back]

2 David M. McCarthy, "Procreation, the Development of Peoples, and the Final Destiny of Humanity," Communio, 26 (1999) 698-721. [Back]

3 Urricchio, W.A. Preface to (Editers; Lanctot, C.A., Martin, M.C., & Shivanandan, M.) Natural Family Planning. Development of National Programs. (Washington, D.C.: International Federation of Family Planning, 1984). [Back]

4 Clubb, E., & Knight, J. Fertility. (Exeter, England: David & Charles, 1999). [Back]

5 Fehring, R.J. "New Technology in Natural Family Planning." JOGN, 20 (May/June, 1991)199-201. [Back]

6 European Study Group. "European Multi-center Study of Natural Family Planning (1989-1995): efficacy and drop-out. The European Natural Family Planning Study Groups." Advances in Contraception 15 (1999) 69-83. [Back]

7 Howard, M.P. & Stanford, J.B., "Pregnancy Probabilities During Use of the Creighton Model Fertility Care System." Archives of Family Medicine, 8 (Sept./Oct. 1999) 391-402. [Back]

8 Hatcher, R.A., Trussell, J., & Stewart, F. et al. Contraceptive Technology. 17th Revised Edition. (New York: Ardent Media, Inc., 1998). [Back]

9 Larimore, W.L.& Stanford, J.B., "Post-fertilization Effects of Oral Contraceptives and Their Relationship to Informed Consent." Archives of Family Medicine, 9 (Febr. 2000) 126-33. [Back]

10 Rivera, R., Yacobson, I., & Grimes, D. "The Mechanism of Action of Hormonal Contraceptives and Intrauterine Contraceptive Devices." American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 181 (1999)1263-69. [Back]

11 Trussell, R. "Contraceptive Efficacy," Chapter in Contraceptive Technology . (New York: Ardent Media, 1998):779. [Back]

12 Harlup, S., Kost, K., & Forrest, J.D. Preventing Pregnancy, Protecting Health: A New Look at Birth Control Choice in the United States. (New, York: The Alan Guttmacher Institute, 1991). [Back]

13 Azbell, B. The Pill. (New York: Random House Books, 1995). [Back]

14 Shane, B. Family Planning Saves Lives. Third Edition. (Population Reference Bureau, Washington, D.C., 1997). [Back]

15 Ory, H., Forrestr, J.D., & Lincoln, R. Making Choice; Evaluating the Health Risks and Benefits Of Birth Control Methods. (The Alan Guttmacher Institute, NewYork, NY, 1983). [Back]

16 Fagen, P.F. "A Culture of Inverted Sexuality." The Catholic World Report (Nov. 1998) 56-63. [Back]

17 Pope Paul VI, On The Regulation of Birth, (Washington, D.C.: United States Catholic Conference, 1968). [Back]

18 Antonisamy, A.S. Wisdom for All Times: Mahatma Gandhi and Pope Paul; VI On The Regulation of Births (Pondicherry, India: Family Life Service Center, 1978) 22. [Back]

19 Keats, C. "Does Abstinence Make the Heart Grow Fonder?" U.S. Catholic, 62 (June 1997) 32-38. [Back]

20 Marshall, J. Love One Another: Psychological Aspects of Natural Family Planning, (London: Sheed & Ward, 1995). [Back]

21 Shivanandan, M. "Reader's Reviews." NFP Forum, 7 (Fall 1996) 6-9. [Back]

22 Westoff, C.F., & Ryder, N.R. "Conception Control Among American Catholics," Chapter in (Liu, W.T. & Pallone, N.J. Editors) Catholic/ USA; Perspectives on Social Change. (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1970) 257-68. [Back]

23 Fehring, R, & Schlidt, A. "Trends in Contraceptive Use Among Catholics In the United States: 1988-1995." Linacre Quarterly (In Press). [Back]

24 Piccinino, L.J., & Mosher, W.E. "Trends in Contraceptive Use in the United States: 1982-1995." Family Planning Perspectives, 30 (1998) 4-10,46. [Back]

25 Center for Health Statistics Divorce Rates: http://www.cdc.gov/nchswww/ fastats/divorce.htm. [Back]

26 Division of STD Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance, 1997. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service. (Atlanta: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [CDC], September, 1998). [Back]

27 Koonin, L.M. & Smith, J.C., Legal Induced Abortion, Reproductive Health of Women. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Services (Atlanta: Center for Disease Control and Prevention, 1995). [Back]

28 Gold, R.B., Abortion and Women's Health. (The Alan Guttmacher Institute: New York & Washington, D.C., 1990). [Back]

29 Moore, K.A. Nonmarital Childbearing in the United States. In Report to Congress on out-of-wedlock Childbearing, Department of Health and Human Services (September, 1995). [Back]

30 Fukuyama, F. "The Great Disruption," Atlantic Monthly, p. 72, May, 1999. [Back]

31 McCLory, R. Turning Point. (New York: The Crossroad Publishing Co., 1995). [Back]

32 Marshall, J & Rowe, B.J, "Psychological Aspects of the Basal Body Temperature Method of Regulating Birth." Fertility and Sterility, 21 (1970):14-19. [Back]

33 Borkman, T, & Shivanandan, M. "The Impact of Natural Family Planning on Selected Aspects of the Couples' Relationship." International Review of Natural Family Planning, 4 (1984) 58-66. [Back]

34 Fragstein, M, Flynn, A., & Royston, P. "Analysis of a Representative Sample of Natural Family Planning Users in England and Wales, 1984-1985." International Journal of Fertility, Suppl. (1988) 70-77. [Back]

35 Klann, N, Halwig, K., & Hank, G. "Psychological Aspects of NFP Practice." International Journal of Fertility, Suppl. (1988) 65-69. [Back]

36 Boys, G., "Factors Affecting Client Satisfaction in the Instruction of Natural Methods." International Journal of Fertility, Suppl. (1988) 59-64. [Back]

37 Aguilar, N, The New No-Pill No-Risk Birth Control, (New York: Rawson Associates, 1986). [Back]

38 Kippley, J. The Art of Natural Family Planning, (The Couple to Couple League International, Cincinnati, Ohio, 1998). [Back]

39 Tortorici, J. "Conception Regulation, Self-esteem, and Marital Satisfaction among Catholic Couples: Michigan State University Study." International Review of Natural Family Planning, 3 (1979)191-205. [Back]

40 Fehring, R, Lawrence, D., & Sauvage, C. "Self-esteem, Spiritual Well-being, and Intimacy: A Comparison among Couples Using NFP and Oral Contraceptives." International Review of Natural Family Planning, 13/3-4 (1989): 227-36. [Back]

41 Fehring, R., & Lawrence, D. "Spiritual Well-being, Self-esteem, and Intimacy among Couples Using Natural Family Planning." Linacre Quarterly, 61/3 (August 1994)18-29. [Back]

42 Oddens, B.J. "Women's Satisfaction With Birth Control: A Population Survey of Physical and Psychological Effects of Oral Contraceptives, Intrauterine Devices, Condoms, Natural Family Planning, and Sterilization Among 1466 Women." Contraception, 59 (1999) 277-86. [Back]

43 Bedeilan, A.G., Geagud, R.J., & Zmud, H. "Test-retest Reliability and Internal Consistency of the Short Form of Coopersmith's Self-esteem Inventory." Psychological Reports, 41 (1977)1041-42. [Back]

44 Frerichs, M. "Relationship of Self-esteem and Internal-external Control to Selected Characteristics of Associate Degree Nursing Students." Nursing Research 22 (1973) 350-52. [Back]

45 Schaefer, M.T., & Olson, D. "Assessing Intimacy: The PAIR Inventory." Journal of Marital and Family Therapy, 7 (1981) 46-70. [Back]

46 Paloutzian, R & Ellison, C. "Loneliness, Spiritual Well-being and Quality of Life." In L. Peplau & D. Perlman, eds. Loneliness: A Source Book of Current Theory, Research and Therapy (pp.224-237). John Wiley and Sons, New York, 1982. [Back]

47 Woodsong, C & Koo, H.P. "Two good reasons: women's and men's perspectives on dual contraceptive use." Social Science & Medicine, 49 (Sept. 1999) 567-80. [Back]

48 Dietrich, B. "High Tech Ways to Natural Family Planning." Student Paper in Health 198 - Natural Family Planning (Fall 1999) Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI. [Back]

49 Hogan, R., & LeVoir, J.M., Covenant of Love: Pope John Paul II on Sexuality, Marriage, and Family in the Modern World (San Francisco: Ignatius Press, 1992). [Back]

50 Bork, H.B. Slouching Towards Gomorrah: Modern Liberalism and American Decline (New York: ReganBooks, 1996). [Back]

51 Chaput, Charles J. Of Human Life, A Pastoral Letter to the people of God of northern Colorado on the truth and meaning of married love. July 22, 1998. [Back]

52 Fehring, R., Cheever, K, German, K & Philpot, C. "Religiosity and Sexual Activity among Older Adolescents." Journal of Religion and Health, 37 (Fall 1998) 229-48. [Back]

53 Hartmen, C., Physicians Healed. (One More Soul, Dayton Ohio, St. Martin, de Porres, New Hope, KY: 1998). [Back]

54 Schonhoff, A. "Natural Family Planning: An Educated Choice." Student Paper in "Health 198 - Natural Family Planning" (Fall 1999) Marquette University, Milwaukee, WI [Back]

Article copyrights are held solely by author.

[ Japan-Lifeissues.net ] [ OMI Japan/Korea ]