The Need to "Say It"

I am fortunate to have been given the opportunity to teach philosophy to some of the best and brightest teenagers in the city. What continues to puzzle me about them, however, is their almost complete lack of confidence in what they already know. When questioned on what I taught them previously, they are very hesitant to say what they know to be true. Some will whisper the answer to a neighbour, or utter it just under their breath, loud enough for me to hear it, but not loud enough for me to determine who said it - in case they happen to be wrong. And if someone takes a risk and provides me with the answer that appears true to them - because it is true - , all I have to do is appear slightly skeptical of their answer, and they backtrack, even when they had it right.

How will they survive the secular environment of the university? I often wonder. All it will take is one professor with an inflated ego and a secular mind to dash to pieces everything that our students suspect is true.

This insecurity does not necessarily come to an end with the end of adolescence. I know of a Catholic woman who knew all sorts of things about right and wrong, but she too lacked the confidence to declare definitively to her husband what she believed she understood to be the real implications of her commitment to marry in the Church. It was only when she heard someone else "say it", that is, point out what is right and what is wrong in her situation, that she came alive, agreeing, indicating what she'd thought that was the truth, but wasn't sure of herself enough to say it.

This phenomenon is perfectly understandable when we consider the air we've been made to breathe in this culture for the past 40 years. People have been told through film, television, newspaper, novels, as well as by political leaders and Supreme Court justices, that there is no clear demarcation between what is truly good and truly evil, that is, between what is true and false. Call it the new orthodoxy, or post-modernism, or post-modern relativism; it is all the same: nihilism in one form or another. It is the air we've been breathing for decades, and the effects are obvious: what were traditionally, definitively, and almost universally regarded as sinful, wrong, depraved, etc., are now only so for persons of a particular and private worldview, and the latter now hesitate to attribute any certainty and universal scope to what they apprehend as true or false, right or wrong.

All is not lost, however, because cultures change, while human nature endures. Truth is the food of the intellect, and the human mind hungers and thirsts for it. Although truth is multifaceted and even multilayered, it is nonetheless a conformity between what is in the mind and what is real, objective, and larger than the self. Moreover, truth is beautiful; it tweaks our sense of wonder, and man has a natural inclination to behold the beautiful. Although the culture has for decades been looking over our shoulder, assuring us that the beauty we behold exists in our eyes only, that the truth we contemplate is but a construct, and that good and evil are merely societal conventions that outline what we like and what we don't, we still delight in what is objectively true, beautiful and good, despite what we've been told. Yet we're still ambivalent.

This is an unhealthy state of affairs for Catholics, and there is probably a greater need now than in any other period in the 20th century to have the concrete moral implications of the gospel spelled out in very clear and unambiguous terms; for children cannot hope to play a game of baseball without foul lines and a determinate set of rules, and before they can begin to play, they have to know where are the foul lines and just what those rules are. The world has been telling them that they can make their own. Christ, however, calls us to be children and to freely enter into the game of divine grace. But if children are not given the rules, they will invent their own, thus entering into an entirely different game - theirs, not God's.

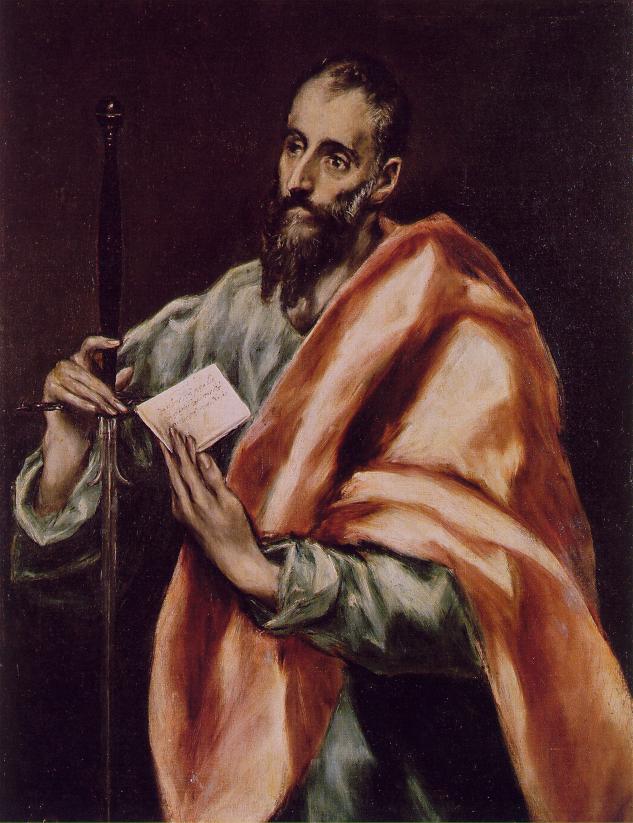

If we examine the letters of St. Paul, we discover that he didn't hesitate to explicitly link the faith we profess to the moral implications of that faith in Christ. In his Letter to the Ephesians, he writes:

I declare and solemnly attest in the Lord that you must no longer live as the pagans do -- their minds empty, their understanding darkened. They are estranged from a life in God because of their ignorance and their resistance; without remorse they have abandoned themselves to lust and the indulgence of every sort of lewd conduct. That is not what you learned when you learned Christ!...See to it, then, that you put an end to lying; let everyone speak the truth to his neighbour, ...The man who has been stealing must steal no longer; ...Do nothing to sadden the Holy Spirit with whom you were sealed against the day of redemption.

But Paul does not stop here, as if to assume the reader can figure out the rest for himself. He continues, providing examples that make explicit the kind of behaviour that "saddens the Holy Spirit".

Get rid of all bitterness, all passion and anger, harsh words, slander, and malice of every kind...As for lewd conduct or promiscuousness or lust of any sort, let them not even be mentioned among you; your holiness forbids this. Nor should there be any obscene, silly, or suggestive talk; all that is out of place. Instead, give thanks. Make no mistake about this: no fornicator, no unclean or lustful person - in effect an idolater - has any inheritance in the kingdom of Christ and of God. Let no one deceive you with worthless arguments.

It is true that some people come to Church to pray their way away from God, and so are most indignant to hear anyone delineate basic moral truths that they regard as unjust limitations on the game they've invented for themselves. But most come in search of clarity, direction, and meaning. To feed them is a work of charity.

Article copyrights are held solely by author.

[ Japan-Lifeissues.net ] [ OMI Japan/Korea ]